By Cherian George and Minos-Athanasios Karyotakis

Academia as an industry has come to rely on journal impact factors as convenient proxy measures of faculty members’ research quality. As competition intensifies — among individuals, departments, and universities — such bibliometrics have grown in importance. At many institutions, researchers are pushed to publish in journals that are highly ranked.

Many scholars of non-western societies have long noted, though, that “top-tier” journals, while international in reputation, are far from global in orientation. This is an issue that we and our colleagues in the Global Media Studies Network are keen to discuss.

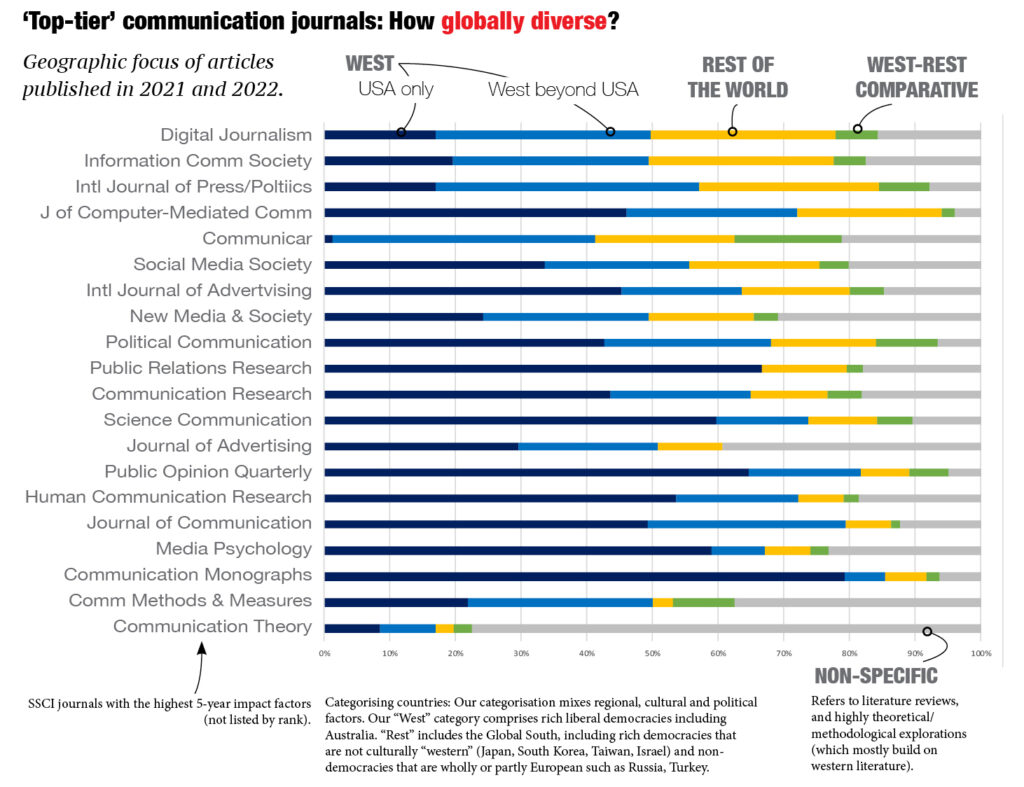

First, though, what exactly is the current state of affairs? We looked at 20 SSCI-indexed communication journals with high five-year journal impact factors. We categorised all the articles they published in 2021 and 2022 according to their geographic focus: what country or countries was each article studying?

Here is what we found:

This snapshot shows clearly that top-tier journals generally have a geographic diversity problem. Most of the articles are about the west, with a high proportion of articles focusing purely on the United States. Also striking is the lack of North-South comparative work, despite years of advocacy for comparative research.

The chart may underestimate the imbalance. We coded many of the articles — literature reviews, meta-studies, or purely methodological or theoretical pieces — as geographically “non-specific” as they have no explicit focus on any particular country, but since these tend to be built on past work that was even less diverse than the field is now, most of these should probably be considered genetically western.

One interesting pattern is that journals devoted to digital communication host a higher proportion of non-western work. This could be because the digital is so globalised and new that research on phenomena beyond the west (say, disinformation in Kenya’s social media) is intelligible to western editors, while research on older offline phenomena (say, caste discrimination on Indian television) requires extensive contextual explanation that journals do not have the patience for. The digital may also be more amenable than offline communication to the quantitative research methods favoured by many top journals.

While the overall picture may be quite clear, what to make of it is debatable.

One possible reading is that the imbalance is a fair reflection of a capability gap. Perhaps scholarship on non-western societies is empirically, methodologically, and theoretically less developed? At least implicitly, many university administrators employing bibliometrics in the Global South appear to agree with this assessment: they seem to think there is nothing wrong with these journals or their top-tier status, so their employees just need to work harder.

Fortunately, we know many editors of top journals who disagree with that theory. They acknowledge their blindspots and have been trying to globalise their output by, for example, diversifying their editorial boards. Note that we did not content-analyse these journals over time. It is possible that they were even less globally diverse a decade ago, and that what we see now represents progress. If so, we should ask those that have made the biggest strides how they did it, so that we can share best practices. Equally, we need to discuss why some journals have not succeeded despite sincere efforts. For example, could well-meaning benchmarks of methodological rigour have the unintended effect of locking out work from societies where data is too scarce for sophisticated quantitative studies?

Finally, our snapshot raises questions about the practice of ranking journals based on seemingly objective bibliometrics that are blind to global diversity. Journals are free to choose their own orientations. Just as there are journals dedicated to Asia or Africa, it is understandable if an American journal wants to focus on its home turf. Perhaps the real problem is academia’s desire to place journals in a pecking order that does not acknowledge geographic biases.

Your thoughts?

If you research non-western contexts (or know others who do), please use our questionnaire to tell us what you think individual researchers, departments, associations, and editors/publishers can do to make the field’s journals and book publishers less western-centric and more globally diverse. With your permission, we will share your thoughts in future publications and at our ICA panel in May.

Join us at ICA Toronto

BLUE SKY BIG IDEAS SESSION

Globalising research and teaching of media and communication studies

Panelists: Saba Bebawi, Cherian George, Silvio Waisbord, Herman Wasserman

Monday 29 May, 1:30–2:45pm, Toronto, Canada

The convenors of the Global Media Studies Network will lead a conversation at the International Communication Association Annual Conference in Toronto about diversifying, de-westernising and decolonising the field.